One of the most effective ways to communicate science to the general audience is through stories. Everyone loves them. In films, music, and theaters, artists have long experimented on and perfected the crafts of spreading ideas and emotions at the same time. Perhaps, we, scientists, can master such art as well.

INTRODUCING CHARACTERS

Lehman Engel, a former Broadway director, walked on a beach. He saw a dreary pelican flying, looking for fish. What a poor bird. But soon, it dived and emerged with one in its mouth. Lehman thought, "There was no doubt that I was on its side because I had met the pelican first." So, what if he was snorkeling underwater, mesmerized by a beautiful blue fish? And suddenly, the pelican struck. Oh no! • Broadway musicals like Anastasia typically present their main characters, and life goals, early in the story. The audience then decides whom to root. Their choices depend on the perspective given, which is framed by the sequence and length of introduction. How could we benefit from Lehman's inspiration? • We tell stories about nature. Explaining observations is not straightforward because there are always competing hypotheses: the null and the alternatives. These are our characters. Anyone has a chance of surviving hypothesis tests. However, the null, maybe because of its simplicity and or dreariness, often lies in the shadow of the alternatives. The lack of stage time can instill a sense of failure when all the alternatives get falsified in the end. But, what if we change our perspective at the beginning? We can satisfy the audience by making their beloved character the winner.

PLOTTING THE PIECES

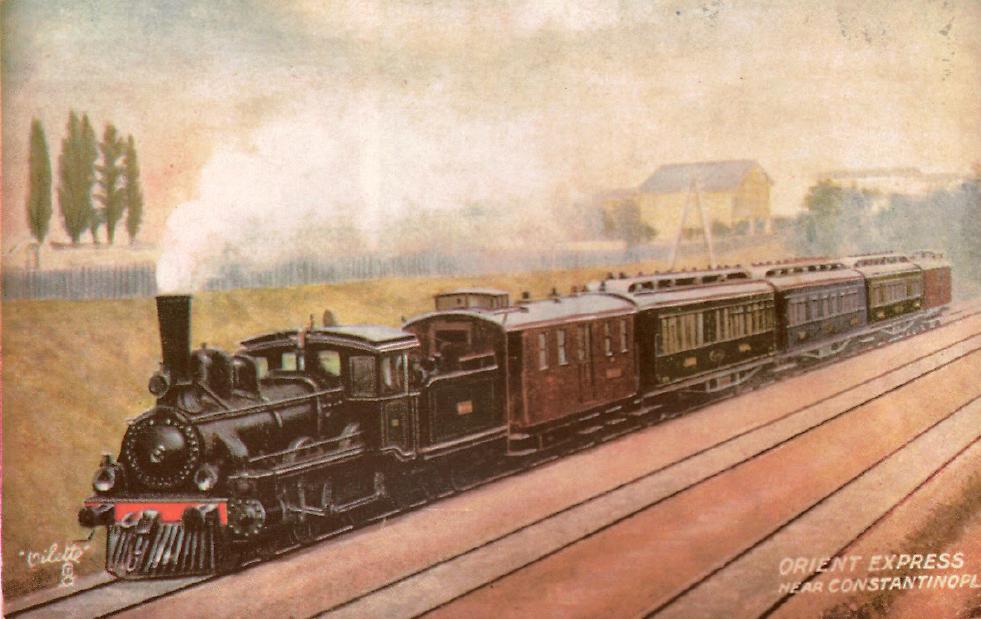

What makes a murder-mystery novel like Murder on the Orient Express so compelling that it grips readers to finish it in one or two sittings? Why does Detective Hercule Poirot request each train passenger whom he interviews to write their signatures? • A murder is simple. What makes it complicated is that we never learn about it all at once. Building the puzzle, Agatha Christie chops her story into matching pieces—a clue and an answer—and orders them into a neat sequence. Confusions go to the beginning and resolutions to the end. Readers won't be able to sleep until the puzzle is complete. • The manuscript outline fits this clue-answer system. More than a hook, the introduction props the discussion. Readers become excited by collecting clues and sensing looming awe, but all have to pay off at the end. Soil scientist Joshua Schimel best presents this idea as a structure familiar among journalists: the hourglass. The discussion on the results and significance of a research project should match the promise. Wouldn't we feel cheated if the conclusion springs from nowhere? Or when it fails to close all loops? But if plotted well, the intro and discussion couple makes for a satisfying ride.

coming soon

REFERENCES

Bajekal, N. 2016. Titanic and Avatar Producer Jon Landau on What All Great Movies Have in Common. Newsweek.

Christie, A. 1934. Murder on the Orient Express. Collins Crime Club: London. UK.

Engel, L. 1972. Words with Music: The Broadway Musical Libretto. Schirmer Books: New York, NY.

Schimel, J. 2011. Writing Science: How to Write Papers That Get Cited and Proposals That Get Funded. Oxford University Press: New York, NY.

Images (from top to bottom) by Producers of Anastasia The Musical (CC BY-SA 4.0), Mary Evans Picture Library (public domain [PDM]), and Claude Monet (PDM).